Why we are all pushed - whether we like it or not.

- You take the salad first in the canteen because it's at the beginning.

- You click on "Accept all", even though you are actually skeptical.

- You decide more quickly if an option is marked as "particularly popular".

These little nudges are called nudges.

They change our behavior without forcing us. Discreet, but often surprisingly effective.

Some happen casually. Others are deliberate.

What they have in common: They influence decisions - every day, everywhere, often unnoticed.

And that's exactly why it's worth taking a look at the mechanics behind it.

For those who understand how nudging works can not only recognize it, but also use it.

Table of contents

Nudging explained: psychology that works

Nudging changes decisions, but not through coercion or rewards.

A small, targeted impulse is often enough to steer behavior in a certain direction. Without excluding alternatives. Without pressure.

Psychologically, nudging is based on a simple principle:

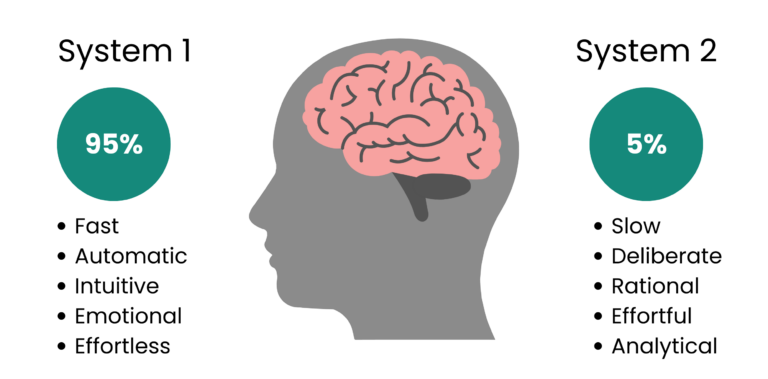

We think in two modes. Daniel Kahneman describes these as System 1 & 2

- System 1 is fast, intuitive, emotional. It reacts immediately.

- System 2 is slow, rational, deliberate - but often sluggish.

In everyday life, System 1 almost always takes the wheel.

And this is exactly where nudges come into play: they shape the framework in such a way that System 1 automatically tends towards the desired decision - without us consciously noticing or thinking about it.

Nudging in UX design

Nudging happens all the time, especially in digital interfaces.

Not through loud effects, but through details that guide our decisions. Colors, wording, layouts. What seems like a small design detail can be decisive in the end.

In the UX world, this is often referred to as behavior patterns.

These are recurring design patterns that have a targeted effect on our behavior - for example, by making decisions easier, building trust or creating urgency. Nudging is therefore not an add-on, but already part of many designs. The only question is: is it used consciously?

Typical nudging elements in UX design:

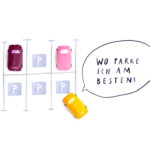

- Defaults: Pre-selected options such as newsletter opt-ins or payment methods - convenient for users, but with a strong steering effect.

- Visual highlighting: Colors, sizes, contrasts. What stands out is more likely to be chosen.

- Labels & microtexts: A short note such as "Recommended" or "Only 3 left" changes the perception immediately.

- Framing: Whether something appears as "20 % more expensive" or as "80 % cheaper" has a massive impact on the valuation.

- Social Proof: Information such as "More than 1,000 customers have bought" activates our need for security.

- Progress Bars: When progress becomes visible, the motivation to complete a process increases.

These mechanisms are familiar from conversion optimization - but in the context of nudging, they are considered more consciously:

Not just as a design tool, but as an influence on behavior.

And that is precisely why we need clarity in dealing with it.

Because where does targeted steering begin - and where does it become unfair pressure?

Nudging ≠ Dark Pattern

A fairly set impulse makes a decision easier. A dark pattern pushes users in a direction that they would not have chosen themselves - often through misleading or lack of transparency.

So the crucial question is not only: Does the nudge work?

But also: Is it justifiable?

A/B testing meets nudging

A nudge can influence a decision. But does it work the way you expect it to?

Just because a measure sounds psychologically plausible does not mean that it will work in practice.

Therefore, the following applies to UX and conversion design:

Nudges need tests. Without valid data, a nudge is just a hypothesis.

This is exactly what A/B testing allows you to check. You specifically test a psychological intervention against a neutral or alternative variant

For example:

- A price offer with a "Recommended" label vs. an identical offer without a label

- A call-to-action with reference to scarcity ("Today only") vs. a factual CTA

- A preselected default in the form vs. an empty selection

What you can measure: Click rate, conversion, bounce rate, time to decision - depending on the context also trust, satisfaction or willingness to interact.

The decisive factor:

Not every nudge has the same effect on every target group or application.

What works for a store can fail in SaaS onboarding. What works for new customers can irritate regular users.

This creates real added value for product and marketing teams:

Nudging is no longer used purely intuitively, but on the basis of reliable data.

A/B testing can be used to find out which intervention really works and which does not.

Ethics in nudging

Nudging influences decisions. That is its strength - but also its risk.

Because those who guide behavior intervene. Not roughly, not with coercion, but noticeably. And that is precisely why sooner or later the question arises: Is this allowed?

There is often a fine line between a helpful nudge and a manipulative pattern.

One example:

A pre-set tick for the newsletter can be practical because it reduces the effort for interested parties. However, if it is deliberately hidden or provided with confusing wording, it becomes a dark pattern.

What matters is the intention behind the design.

Is the nudge in the user's interest?

Do they understand what is happening? Is there real freedom of choice?

Or are they being pushed without realizing it?

- Transparency: Users should be able to understand how a decision is influenced.

- User well-being: Ideally, a nudge should not only increase conversion, but also offer real added value.

- Context sensitivity: Not every impulse fits every situation. Restraint is required, especially when it comes to sensitive topics such as finances or health.

Conclusion

Nudging is an effective tool for influencing behavior in a targeted manner. It can simplify decisions, provide orientation and improve user guidance.

But impact alone is not enough.

A nudge is only useful if it is comprehensible, fair and designed in the interests of the user. And only when it is tested will it become clear whether it really works.

This is precisely where the strength of A/B testing lies. Psychological hypotheses can be tested based on data. This turns an idea into a well-founded measure and design into a measurable strategy.

For teams developing digital products, this is a clear opportunity:

Nudging becomes plannable, comprehensible and measurable.

What counts is not the theory, but the effect, backed up by real data.

Anyone who takes responsibility seriously tests what they design.

Because good UX design doesn't make decisions for users, it helps them to make better decisions.

Individual references

- Thaler, R. H., & Sunstein, C. R. (2009). Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. New York: Penguin Books. [Accessed on: 14.04.2025]

- Kahneman, D. (2011): Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. [Accessed on: 14.04.2025]

Further psychological triggers

Halo effect

The halo effect ensures that a single quality influences the entire image.

To the article about the halo effect.

Scarcity

The feeling that something could soon no longer be available arouses desire.

Dunning-Kruger effect

The effect describes how people with little experience overestimate their abilities.

Framing effect

The way in which information is presented significantly shapes perception.

Mere exposure effect

The more often we see, hear or experience something, the more we like it.

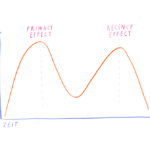

Primacy effect

The first piece of information remains most strongly in our memory and shapes our perception.

Diderot effect

The effect describes how a new purchase awakens the desire to buy more suitable products.

Paradox of Choice

Many options can seem overwhelming. Few options simplify the decision.

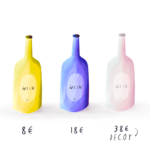

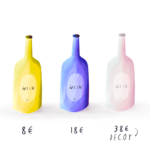

Decoy effect

When we are presented with an unattractive option, the more attractive alternative seems even more tempting

Affect heuristics

Quick decisions are often guided by strong feelings rather than rational considerations.

Social Proof

Endowment effect

People tend to attribute a higher value to things just because they are in their possession.

Nudging

Nudging uses small incentives to subtly guide behavior without restricting freedom of choice.

New

The way in which information is presented significantly shapes perception.

New

When we are presented with an unattractive option, the more attractive alternative seems even more tempting